Siena

The ancient Via that in the Middle Ages united Canterbury in Rome and the ports of Puglia has been rediscovered by modern travelers, who walk along a gorgeous and surprising path. Since 2001, the European Association of the Vie Francigene coordinates the development and enhancement of an itinerary that crosses Italy and Europe, tracing the history of our continent.

There are over a thousand kilometers to travel in Italian territory, from the Passo del Gran San Bernardo to Rome, step by step. Easy mountain trails, stone muleways, country roads and less traffic, no traffic, white roads among cypresses, or shaded by solemn domestic pines. Below your feet are the oldest roads of the Bel Country, the carriageways with the river cobblestones, the passageways, the sanpietrini of Rome. Medieval pavements and the Cassia street basalt. The trails guide you through the country where all the roads lead to Rome: the official route of the Via Francigena is the safest, easiest way, without technical difficulties, carefully studied to be run by everyone and all ages.

HISTORY

In the Middle Ages, around the 7th century, the Longobards contended the Italian territory with the Byzantines. The strategic need to connect the Kingdom of Pavia and the southern ducats through a sufficiently secure route led to the choice of a lesser-lesser itinerary, which went through the Apennines at the current Pass of Cisa, and after the Valle del Magra He moved away from the coast in the direction of Lucca. From here, not to get too close to the Byzantine areas, the trail continued to the Elsa Valley to arrive in Siena, and then through the valleys of Arbia and d’Orcia, to reach the Val di Paglia and the Lazio territory, Where the track was entered in the ancient Via Cassia leading to Rome. The route, named “Via di Monte Bardone”, from the ancient name of the Passo della Cisa, Mons Langobardorum, was not a real street in the Roman sense or even less in the modern sense of the term. In fact, after the fall of the empire, the old consular lines fell into disuse, and except for a few lucky cases, they ended up in ruins, “ruptures”, so that the use of the word “broken” dates back to that time to define the Direction to take.

The street area

The Roman castles gradually left the place of trails of trails, traces, tracks crossed by the passers-by, which generally spread over the territory to converge at the work (residential or hospitable centers where there was accommodation for the night), or at Some obligatory passages such as crossings or wagons. More than roads were, therefore, “street areas”, the path of which varied due to natural causes (overpopulations, landslides), for changes in the boundaries of the crossed territories and the consequent demand for gabelles for the presence of brigands. The bottom was paved only at the crossing of the inhabited centers, while the connecting sections prevailed the beaten ground.

It therefore appears clear that the reconstruction of the “true” route of the Francigena Street would now be an impossibility, since this has never existed; instead, it is important to find the main jobs and the main places touched by the travelers along the Via.

The Francigena Way is born

When the Longobard domination left the Franks, the Via del Monte Bardone changed its name to Via Francigena, or “a road originating from France”, the latter which, in addition to the present French territory, included the Rhine Valley and Netherlands.

At that time, traffic along the Way was also growing as the main linkage between North and South of Europe, along which merchants, armies, and pilgrims crossed.

THE LENGTH AT THE TIME

Between the end of the first millennium and the beginning of the second, the practice of pilgrimage became increasingly important. The holy places of Christendom were Jerusalem, Santiago de Compostela, and Rome, and the Francigena Street was the central junction of the great ways of faith. In fact, pilgrims from the north traveled the way to Rome, and then continued along the Appian Way to the Apulian ports, where they embarked towards the Terrestrial. On the other hand, Italian pilgrims to Santiago traveled to the north to arrive at Luni, where they embarked at the French ports or to continue to the Moncenisio, and then into Tolosan Street, which led to Spain. Pilgrimage soon became a mass phenomenon, and this enhanced the role of the Francigena Way, which became a decisive communication channel for the realization of the cultural unity that characterized Europe in the Middle Ages.

Itinerary sources

It is mainly thanks to travel diaries, and in particular to the notes of an illustrious pilgrim, Sigerico, that we can reconstruct the ancient path of Francigena. In 990, after having been ordained Archbishop of Canterbury by Pope John XV, the Abbot returned home by annotating on two manuscript pages the 80 jobs he stayed for an overnight stay. The Sigerico diary is still considered the most authoritative itinerary source, so much so that it is often referred to as “Via Francigena according to the Sigerico route” to define the most “philological” version of the route.

Growth and decline of the Via Francigena

The growing use of Francigena as a way of commerce led to the exceptional development of many centers along the way.

The Via became strategic to transport goods from the Orient (silk, spices) to the markets of northern Europe, and trade them, usually at the Champagne fairs, in Flanders and Brabant. In the thirteenth century, commercial traffic grew to such an extent that many alternative routes were developed to the Francigena Street, which therefore lost its characteristic of uniqueness and split into numerous connecting routes between the north and Rome.

So much so that the name changed to Romea, since it was no longer the origin, but the destination. In addition, the growing importance of Florence and the centers of the Arno Valley moved to the Orient, until the Bologna-Florence route relegated the Cisa Pass to a purely local function, decreasing the end of the ancient path.

LA VIA FRANCIGENA

Move the first step on the way to Rome. It does not matter where you are, nor does it matter to be great athletes. The Francigena Street is for everyone, and it is the historical route from the north of Europe to the eternal city. Walk on and follow the footsteps of pilgrims who before the year 1000 went down the peninsula. They came from the British Isles, from the Kingdom of the Franks, from the farthest regions of the Empire. The Alps crossed the Great St. Bernard hill: through the valley of the Aosta valley, the doors of the Bel Country were opened for them with cities full of history and art.

Follow the signs that from Canterbury Cathedral cross over, on Pilgrim’s Way, the English countryside to the cliffs of Dover. In addition to the Manche Channel, the Via goes to the gentle landscape of Picardy and Champagne, dotted with ancient cities: stopping at Reims with its cathedral and Clairvaux abbey. Then you enter the Via Francigena in Switzerland, from Sainte-Croix to Vuiteboeuf, then follow the placid Venoge to Lac Léman. From Lausanne, the Via Francigena winds through the Lavaux vineyards up to the Rhône. From the ancient city of Octodurus, the trail winds through the narrow stretch formed by the wild Dranse to the northern slope of the Great St. Bernard Pass.

The climb to the Alps is gentle and gradual: let yourself be enchanted by the snow-capped bastions towards which you are heading the Via. From the hill of Gran San Bernardo the descent is fast, and you are in a few days in the great spaces of the Po Valley. A walk shipped along the embankment of Po. Visit its cities: Vercelli, Pavia, Piacenza will surprise you. From Fidenza climb to the hill and begin the long climb that leads you to pass the Apennines, among the forests of the Cisa pass. Imagine what excitement the Archbishop Sigerico – whose footsteps are following – the sight of the Mediterranean Sea and the deserted beaches of Versilia. Discover the cities that prosper and rich in the Via: Lucca and its hundred churches, San Gimignano and the towers, Siena lying on its hills.

The Credential

Credential, along with Testimonium, is the fundamental document of the pilgrim. It represents the “pilgrim passport”, attesting to its identity and motivation. The pilgrim must have it with him to be identified as such and have access to the reception facilities along the itinerary. Everywhere he is hosted, he will receive a stamp until he completes his journey.

For those who travel the last 100 km on foot or 200 km by bicycle, Credential allows you to receive the certification of the pilgrimage

Beginning in April 2017, the credential issued by the European Association of Vie Francigene gives a number of additional benefits to pilgrims.

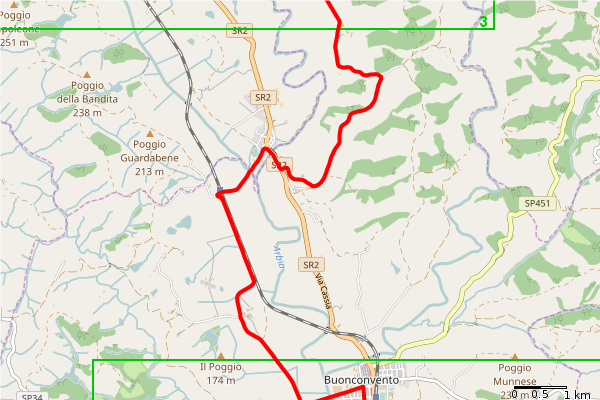

From Siena to San Quirico

Departure Siena, Piazza del Campo

Arrival San Quirico d’Orcia, Collegiate

Total length 54.1 km

Description

If you go on a beautiful sunny day, this stage can become unforgettable thanks to the views

Endless that they enjoy the ridges of the Val d’Arbia, which are run along endless streets

white.

Behind us we can admire the profile of Siena, lying in the hills on the horizon.

The Grancia di Cuna, an ancient barn fortified, is the main historical attraction of this stretch. After the storm we cross Monteroni d’Arbia and Ponte d’Arbia, stopped and

Overtaken Buonconvento, whose historic center is worth a visit, begins the ascent. We go the provincial for

Montalcino, which we leave in order to enter the dream panorama of the Val d’Orcia, along a road route

White door that takes us to Torrenieri. From here we use a section of the dismantled cassia, unfortunately still

Asphalted, to reach San Quirico, which welcomes us with its beautiful collegiate.

Refreshment points and water only in residential areas.

Tav. 02

Italiano

Italiano